Earlier this week, Google DeepMind announced its new research tool AlphaEvolve. Basically, it’s an LLM-driven tool that uses evolutionary algorithms to find solutions for certain math or software problems. It’s already come up with optimizations on a few important problems that could lead to efficiency gains within the AI space and perhaps beyond.

Disclaimer: I haven’t had time to read the whole paper yet, but I’ve managed to read Google DeepMind’s blog post, watch this interview and read a few news articles.

The main limitation of AlphaEvolve is that it can only work on problems where the solution can be evaluated by a machine. So, on the trivial end of things, this might be similar to a LeetCode problem such as “Reverse a linked list”. To solve this, AlphaEvolve would come up with a few solutions and evaluate them for both correctness and efficiency. Obviously, this is the sort of problem that computer science students should be able to solve in their sleep.

Of course, what’s interesting is when you direct AlphaEvolve to work on more interesting problems.

How does it work?

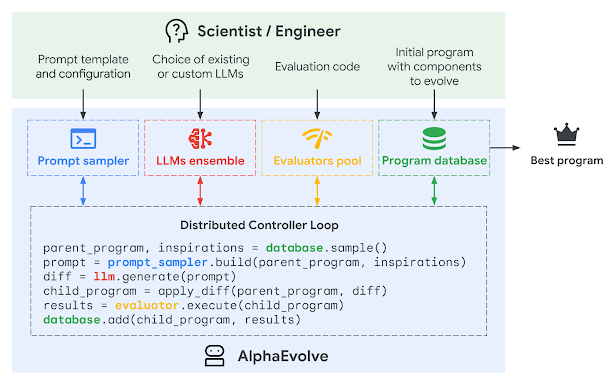

Evolutionary algorithms can solve problems within a large solution-space by tweaking parameters and running many different trials. Selection criteria and evaluation methods can vary, but the general idea is to choose the best solutions from one generation, tweak them a bit, and run a new generation of trials.

Where AlphaEvolve improves on this method of problem-solving is that it uses an LLM to direct progress without relying solely on randomness of the parameters. It also uses automatic code generation so that the parameters tested are (or can be?) code implementations.

The novel thing here is that LLMs aren’t just generating code, they’re guiding the search across a massive algorithmic space. This leads to verifiably novel solutions, not just rediscovering old ones.

What problems can it solve?

AlphaEvolve can only work on problems that can be evaluated by machine. These evaluations can be mathematical correctness, performance metrics, or even physical simulations. The key is that there’s an automated, not human, way to judge success. By taking the human out of the loop, they can run thousands or millions of trials until it finds its solutions.

Despite being limited to this specific type of question, there are a lot of problems in that space, including data center scheduling, hardware design, AI training and inference, and mathematics. In Google DeepMind’s blog post, they said:

“To investigate AlphaEvolve’s breadth, we applied the system to over 50 open problems in mathematical analysis, geometry, combinatorics and number theory. The system’s flexibility enabled us to set up most experiments in a matter of hours. In roughly 75% of cases, it rediscovered state-of-the-art solutions, to the best of our knowledge.”

One of the solutions that has been highly touted is its 48-step universal and recurse-able algorithm for multiplying 4×4 matrices, with major implications for machine learning and graphics. The algorithms are a bit beyond my understanding of linear algebra, but here’s what I’ve gathered:

- If you do it the usual way, you can multiply a 2×2 matrix in 8 steps. Basically, you multiply each number by each of the others and then take the sums.

- There is an optimization to multiply a 2×2 matrix in only 7 steps, and mathematicians have determined that 7 steps is the optimal solution for this problem.

- Because the 7-step algorithm can be done recursively, you can calculate a 4×4 matrix in 7^2 = 49 steps. Basically, you consider the 4×4 matrix as a set of 2×2 matrices and multiply them out.

- AlphaEvolve’s solution is one calculation more efficient than the above 7^2=49 step algorithm. So, on the same problem it should be around 2% more efficient.

- AlphaEvolve’s solution can also be used recursively, so calculating a larger matrix should also be more efficient. I’m not totally clear about how much it would speed things up for which size of matrix.

The reason this seemingly small optimization is so important is that we do a ton of matrix multiplication in machine learning, in both training and inference. So a small difference here can make an enormous difference.

Similarly, one of the other problems that AlphaEvolve worked on was something (we don’t seem to know exactly what, and it’s probably proprietary) that provided Google with an optimization to its data centers that “recovers on average 0.7% of Google’s fleet-wide compute resources”. Given the immense scale of Google’s data centers, this would be a huge sum of money!

Why does it matter?

The major advance here isn’t just speed—it’s novelty. AlphaEvolve didn’t just find better implementations of known algorithms; in some cases, it created ones that are new to science, like the 48-step recursive matrix multiplication.

One of the major criticisms of LLMs has been that, despite their vast reservoir of knowledge, LLMs haven’t really synthesized that knowledge to come up with new discoveries. (To be clear, there have been a few such discoveries from other areas of AI, such as DeepMind’s AlphaFold). Well, now we have an LLM-based method to make those discoveries, albeit only for a specific type of problem.Keeping in mind its limitations, the algorithmic improvements to matrix multiplication alone could generate huge savings in energy, cooling, and environmental damage in the coming years.